|

| Image credit: NASA. |

A joint U.S./Soviet space mission served the political aims of both countries, however, so the concept of a near-term docking mission rapidly gained momentum. In May 1972, at the superpower summit meeting held in Moscow, President Richard Nixon and Premier Alexei Kosygin signed an agreement calling for an Apollo-Soyuz docking in July 1975.

NASA and its contractors studied ways of expanding upon ASTP even before it was formally approved; in April 1972, for example, McDonnell Douglas proposed a Skylab-Salyut international space laboratory (see "More Information," below). A year and a half later (September 1973), however, the aerospace trade magazine Aviation Week & Space Technology cited unnamed NASA officials when it reported that, while the Soviets had indicated interest in a 1977 second ASTP flight, the U.S. space agency was "currently unwilling" to divert funds from Space Shuttle development.

Nevertheless, early in 1974 the Flight Operations Directorate (FOD) at NASA Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, examined whether a second ASTP mission might be feasible in 1977. The 1977 ASTP proposal aimed to fill the expected gap in U.S. piloted space missions between the 1975 ASTP mission and the first Space Shuttle flight.

FOD also assumed that the ASTP prime crew of Thomas Stafford, Vance Brand, and Deke Slayton would serve as the backup crew for the 1977 ASTP mission, while the 1975 ASTP backup crew of Alan Bean, Ronald Evans, and Jack Lousma would become the 1977 ASTP prime crew. FOD conceded, however, that this assumption was probably not realistic. If new crewmembers were needed, FOD noted, then training them would require 20 months. They would undergo 500 hours of intensive language instruction during their training.

FOD estimated that Rockwell International support for the 1977 ASTP flight would cost $49.6 million, while new experiments, nine new space suits, and "government-furnished equipment" would total $40 million. Completing and modifying CSM-115 for its backup role would cost $25 million. Institutional costs — for example, operating Mission Control and the Command Module Simulator (CMS), printing training manuals and flight documentation, and keeping the cafeteria open after hours — would add up to about $15 million. This would bring the total cost to $104.7 million without the backup CSM and $129.7 million with the backup CSM.

The FOD study identified "two additional major problems" facing the 1977 ASTP mission, both of which involved NASA JSC's Space Shuttle plans. The first was that the CMS had to be removed to make room for planned Space Shuttle simulators. Leaving it in place to support the 1977 ASTP mission would postpone Shuttle simulator availability.

A thornier problem was that 75% of NASA JSC's existing flight controllers (about 100 people) would be required for the 1977 ASTP in the six months leading up to and during the mission. In the same period, NASA planned to conduct "horizontal" Space Shuttle flight tests. These would see a Shuttle Orbiter flown atop a modified 747; later, the aircraft would release the Orbiter for an unpowered glide back to Earth. FOD estimated that NASA JSC would need to hire new flight controllers if it had to support both the 1977 ASTP and the horizontal flight tests. The new controllers would receive training to support Space Shuttle testing while veteran controllers supported the 1977 ASTP.

|

| ASTP Apollo spacecraft and Saturn IB rocket sit atop the "milkstool" on Launch Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida. Image Credit: NASA. |

|

| ASTP Soyuz 19 spacecraft and Soyuz rocket lift off from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Soviet central Asia. Image credit: NASA. |

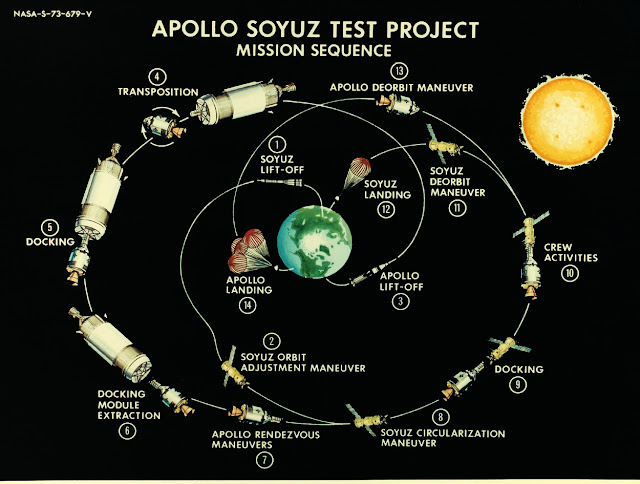

Once in orbit, the ASTP CSM turned and docked with the DM mounted on top of the Saturn IB's second stage. It then withdrew the DM from the stage and set out in pursuit of the Soyuz 19 spacecraft, which had launched about eight hours before the Apollo CSM with cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Valeri Kubasov on board. The two craft docked on 17 July and undocked for the final time on July 19. Soyuz 19 landed on 21 July. The ASTP Apollo CSM, the last Apollo spacecraft to fly, splashed down near Hawaii on 24 July 1975 — six years to the day after Apollo 11, the first piloted Moon landing mission, returned to Earth.

|

| Conceptual illustration of proposed Space Shuttle/Salyut docking. Image credit: Junior Miranda. |

|

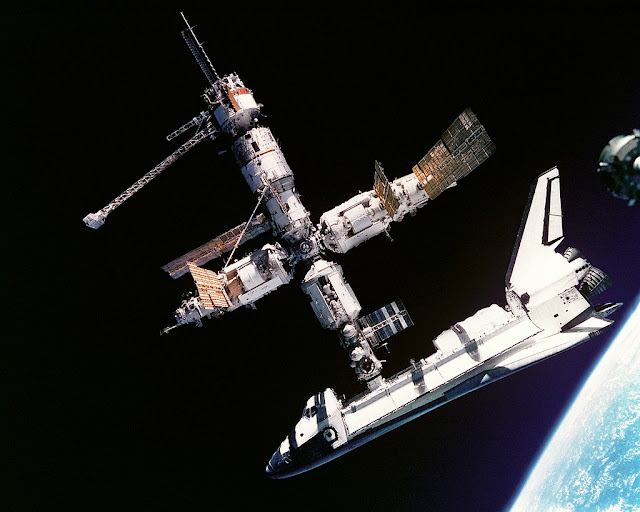

| U.S. Space Shuttle Atlantis docked with the Russian Mir space station, 4 July 1995, as imaged from the Russian Soyuz TM-21 spacecraft. Image credit: NASA. |

In May 1977, the sides formally agreed that a Shuttle-Salyut mission should occur. In September 1978, however, NASA announced that talks had ended pending results of a comprehensive U.S. government review. Following the December 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, work toward joint U.S.-Soviet piloted space missions was abandoned on advice from the U.S. Department of State. It would resume a decade later as the Soviet Union underwent radical internal changes that led to its collapse in 1991 and the rebirth of the Soviet space program as the Russian space program.

Sources

"Second ASTP Unlikely," Aviation Week & Space Technology, 3 September 1973, p. 13.

Memorandum for the Record, "information. . . developed in estimating the cost of flying a second Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) mission in 1977," NASA Johnson Space Center, 4 April 1974.

Thirty Years Together: A Chronology of U.S.-Soviet Space Cooperation, NASA CR 185707, David S. F. Portree, February 1993.

More Information

Skylab-Salyut Space Laboratory (1971)

"Still Under Active Consideration": Five Proposed Apollo Earth-Orbital Missions for the 1970s (1971)

NASA's 1992 Plan to Land Soyuz Space Station Lifeboats in Australia

SEI Swan Song: International Lunar Resources Exploration Concept (1993)

I liked those interim plans, during the transition between Apollo and Shuttle. All the Skylab and Soyuz what-if. A pity CSM-115 & 119 couldn't be flown, but NASA HSF had not only be pared to the bones, the Shuttle sucked every few dollars like a black hole.

ReplyDeleteHi, A: It's refreshing that you say this. Not so many years ago the Shuttle was the ultimate spacecraft because it was what people were used to. Now I don't see too much criticism when I say the Apollo Applications Program (which became Skylab and the J-class Apollos) was the right way to go. dsfp

DeleteI'd think this change in opinion is probably due to the large increase in alt-history with website's like alt-history.com, and how many of the space related stories on them are based on the AAP being funded much more heavily, or just the shuttle in of itself not being funded (Eye's Turned Skyward being the main one). However, I'd say the majority of these stories are more wishful thinking, and even if AAP were funded more, we'd probably still be in a similar area to how we are now, having just took a different path to get here.

DeleteThe early intent (at least as stated) of AAP was to form a bridge to "the next big program." The next program was generally envisioned as a large space station or humans on Mars (less often, a lunar base). Of course, motives behind AAP were probably more to do with keeping the Apollo industrial infrastructure and jobs that attended it in place. Not that different from post-Shuttle, in other words. Myself, I think AAP might have gone the route of Soyuz/Salyut and become firmly entrenched. That's the kind of post-Apollo program I generally depict in my alternate histories. It's a bit cynical - accomplishing anything in space is not the main objective - but I think it is in keeping with our Shuttle experience. dsfp

DeleteWhat could have been

Deletehttps://www.americaspace.com/2023/08/28/lost-moon-reconstructing-the-missions-of-apollos-18-19-and-20-part-1/